The modern zombie genre began in earnest with Richard Matheson’s novel I am Legend and George Romero’s film Night of the Living Dead. Both stories focus on hordes of shambling undead attacking the human survivors of the apocalypse, typically by besieging the shelter of the survivors. From these sources sprang an entire genre of zombie apocalyptic fiction. Romero’s trilogy of Dead films inspired literally thousands of zombie films and novels. The Zombie Movie Database website currently counts over 4600 films which contain zombies. However, the zombie genre also holds great sway in popular culture. Video games like the Resident Evil and Dead Rising series, Dead Island and Killing Floor are all extremely popular, selling millions of copies. Clearly the zombie holds great appeal to both the horror enthusiast and mainstream audiences.

Like the survivalist apocalypses, the zombie story makes the prevailing social institutions incompetent or malevolent, such as the sheriff mistaking Ben for a zombie in Night of the Living Dead or the military using nuclear weapons on a city overrun by zombies in Return of the Living Dead. Many times, the zombie apocalypse is brought on by the old order, either as a government or corporate experiment or accident. Furthermore, any help provided by the government is limited, suspect or worthless, such as plutocracy established in the film Land of the Dead. In any case, the social order quickly collapses and anarchy prevails in the typical zombie genre formula.

Interestingly, both forms of apocalyptic stories make a point to show that the environment itself is not heavily damaged in the process. The zombie genre is dependent on minimal damage to the physical structures of civilization, as the survivors must have grocery stores to loot and malls to take refuge in. The collapse of infrastructure and services such as firefighters apparently do not mean widespread physical destruction. Similarly, survivalists have never foreseen total annihilation, even during the heights of the Cold War, as that would render survivalist training and stockpiling moot (Mitchell 86).

The nature of the Other is greatly dependent on the storyteller’s ideology, which can be seen in both forms of apocalyptic fiction. In survivalist stories, the Other is typically an agent of a corrupt government institution, such as Soviet or UN soldiers or mercenaries under the employ of Zionist bankers. Many times, they are of other races, demonstrating the racist fears of the storyteller. They are cruel and barbaric and espouse anti-American ideology. But even they possess some human traits, as they desire American resources and envy American freedom. Of course, the zombie is the perfect Other. It is human shaped but lacks all the traits they define us as humans. They are unnatural abominations with no place in the natural order of things, so killing them is not only justified, but a merciful act.

The protagonists of these apocalypses are everyman characters, blue collar heroes of modest ambition and means. In the zombie genre, average citizens are thrown into the chaos of the apocalypse, such as Shaun from Shaun of the Dead. Even when the characters are professionals, such as the soldiers and scientists in Day of the Dead, they do not posses pulp fiction levels of ability nor do they stop the apocalypse. They are swept up in the events, helpless to counteract them. The zombie genre demands realism on the part of its human characters, as they are not heroic saviors, but people the audience can identify with. Similarly, survivalists make themselves the protagonists of their apocalypse, able bodied and far from the madding crowds of civilization. Both groups of characters employ bricolage to overcome the Other.

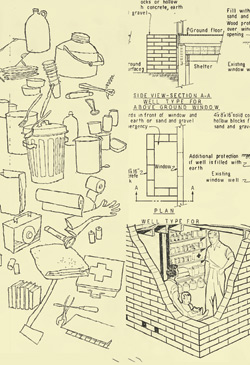

In the zombie genre, survivors routinely build and use improvised tools in order to kill the undead and fortify their shelter. I am Legend’s protagonist has a reinforced home, complete with electricity and the comforts of civilization while the horde claws futilely at the walls. Films like Dead and Breakfast and Dead Alive revel in the gore produced by unleashing jury-rigged weapons of zombie destruction such as a modified lawnmower or jury-rigged shotgun. In most cases, the tools are looted consumer goods and repurposed for the apocalypse. Both Dawn of the Dead and Dead Rising take the ultimate symbol of consumerism, the shopping mall and transform into a fortress and cache of supplies vital to the success of the survivors. The mundane becomes extraordinary.

Bricolage unites both genres more than any other trait, as evidenced by the popular Zombie Survival Guide by Max Brooks. Written in a style nearly identical to U.S. military manuals and survivalist tracts, The Zombie Survival Guide demonstrates how a normal person could survive a zombie attack through training and stockpiling the right equipment. In plain language, Brooks describes the characteristics of zombies, from their sensory abilities to the infective nature of the Solanum virus, which is attributed as the cause of the zombie disease. Unlike other stories of the genre, Brooks describe a wide range of zombie events, from the comparatively small Class 1 to the apocalyptic Class 4 attack. The Guide then describes exact measures on how to survive any class of attack, such as choosing the right kind of weapon, equipment, and developing a long term survival plan. Like other survivalist manuals, it emphasizes the need for training in a wide variety of fields in to guarantee life after the apocalypse, a sentiment shared by survivalists.

It should be noted that the two genres have several key differences, namely in how they portray social dynamics and post apocalyptic life. Survivalists are typically more optimistic about their position after the apocalypse, many believing they will play a vital role in rebuilding civilization while the zombie genre usually portrays a grim downfall of society. However, survivalists are far more distrusting of others and exclude most of society from their plans, many times out of religious or racial prejudices. In the zombie genre, distrust of other survivors inevitably leads to strife and death, as the remaining humans need to work together to survive the onslaught of the undead, as shown in Day of the Dead. When paranoia and hatred outweighs the desire to cooperate, the survivors perish.

Life after the apocalypse seems to be a method of projecting one’s desires for contemporary life. Many survivalists feel marginalized in today’s society, so they create highly detailed stories in which they place themselves as vital actors on center stage of the new world. While the zombie genre does not share that level of optimism, it does emphasizes bricolage as a vital trait for survivors. From this shared theme, we can see that both genres seek to reassert the viability of the consumer class. Survivors do not need to be members of the privileged elite. In fact, it is preferable to remain separate from the institutions that dominated society before the apocalypse, as they will inevitably fail. Survival is dependent on only skill, preparation and the appropriate consumer goods and help from one’s friends and family.

Works Cited

Brooks, Max. Zombie Survival Guide. New York. Three Rivers Press. 2003.

Mitchell, G. Richard. Dancing At Armageddon: Survivalism and Chaos in Modern Times. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 2002.

Strauss, Levi, Claude. The Savage Mind. Chicago. University of Chicago Press. 1962.

Pingback: ParaNorman Is Yet Another Sexist Kids’ Film. Here’s Why. | Lynley Stace

Pingback: Gender Problems In ParaNorman (2012) – Slap Happy Larry